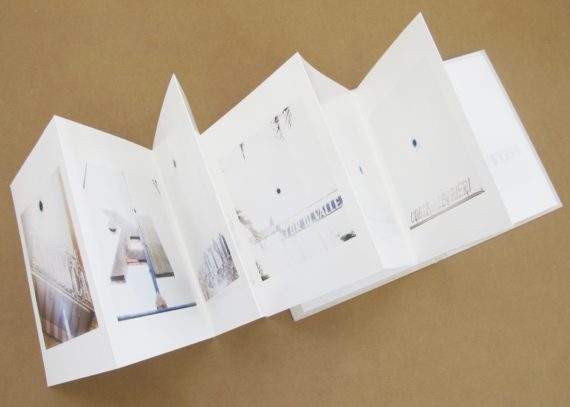

Descrizione

“Marco Delogu is a very experienced photographer. His work usually makes use of sophisticated skills, whether they go through a complex technical apparatus or not. During the summer of 2014, he decided to get back to primitive states of photography. ‘Getting back’ is an inappropriate phrase, as I doubt that he had ever used such means before, especially not when he started. What this ‘turning back’ entails is that Delogu has traveled, artistically, to this point when photography was born, but with all the history of the medium having taken place in the meantime, all his personal history, both as a photographer and as a professional connoisseur of the art of photography, having happened before this starting from scratch, again.

Almost two hundred years ago, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, one of the originators of photography, gave his discovery the name ‘heliography’, i.e. sun writing. The first experiments which he thus designated (from 1826 on) were either artworks or landscapes devoid of any human presence.

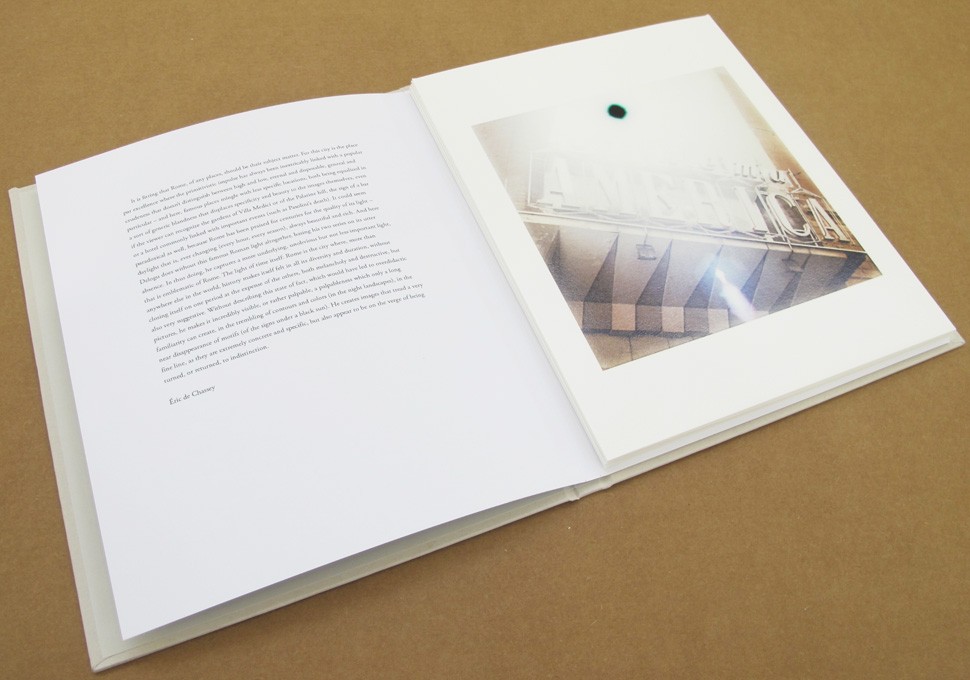

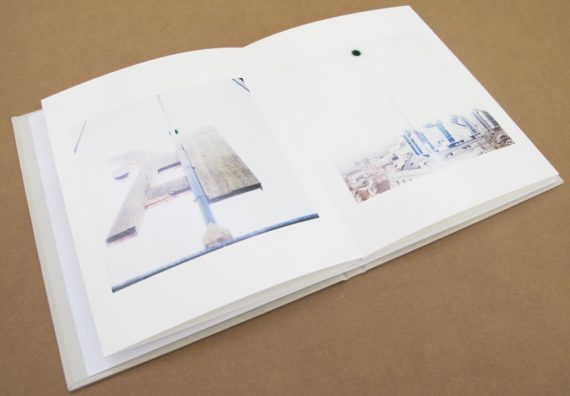

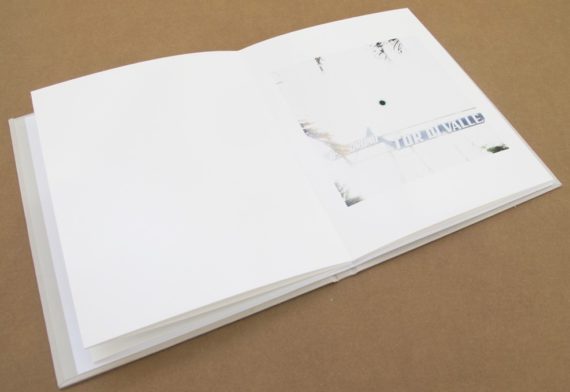

Delogu’s two new series of photographs are paradoxical ‘heliographies’. They do share the primitivistic, technically simple, means of their historical forebear, taking as their subjects nighttime landscapes where no human being can appear, either because of their viewpoints or because of the

time when the locales were shot. But they were also created either without any sunlight (this being replaced by moonlight) or, on the contrary, by directly confronting the sun so that it nearly burns out each and every detail – of the kind that a less direct confrontation usually make visible – leaving as a central mark a dark disk, which the series emphasizes as the recurring and structuring element in each picture. Because of this paradoxical nature, Delogu here produces images that seem to verge on artificiality when they are actually faithful to what has been in front of his camera: a portion of the sky delimitated on one side by large neon or metal signs, themselves burnt by years of being exposed to the sun of this southern city which is Rome, or elements of familiar landscapes blurred and colored by the tenuous and unstable nighttime lights. It is fitting that Rome, of any places, should be their subject matter. For this city is the place par excellence where the primitivistic impulse has always been inextricably linked with a popular crudeness that doesn’t distinguish between high and low, eternal and disposable, general and particular – and here, famous places mingle with less specific locations, both being equalized in a sort of generic blandness that displaces specificity and beauty to the images themselves, even if the viewer can recognize the gardens of Villa Medici or of the Palatine hill, the sign of a bar or a hotel commonly linked with important events (such as Pasolini’s death). It could seem paradoxical as well, because Rome has been praised for centuries for the quality of its light – daylight that is, ever changing (every hour, every season), always beautiful and rich. And here Delogu does without this famous Roman light altogether, basing his two series on its utter absence. In thus doing, he captures a more underlying, unobvious but not less important light, that is emblematic of Rome. The light of time itself: Rome is the city where, more than anywhere else in the world, history makes itself felt in all its diversity and duration, without closing itself on one period at the expense of the others, both melancholy and destructive, but also very suggestive. Without describing this state of fact, which would have led to overdidactic pictures, he makes it incredibly visible, or rather palpable, a palpableness which only a long familiarity can create, in the trembling of contours and colors (in the night landscapes), in the near disappearance of motifs (of the signs under a black sun). He creates images that tread a very fine line, as they are extremely concrete and specific, but also appear to be on the verge of being turned, or returned, to indistinction. “

Éric de Chassey